The Minstrel Show in The Scottsboro Boys

Minstrel show characteristics

The American minstrel show is a musical variety style of entertainment featuring ragtime music and the latest popular dances including tap dance, soft-shoe, and sand dance. It also featured the popular songs of the period, as well as comedy sketches and farcical skits. It is the forerunner to vaudeville and musical theater.

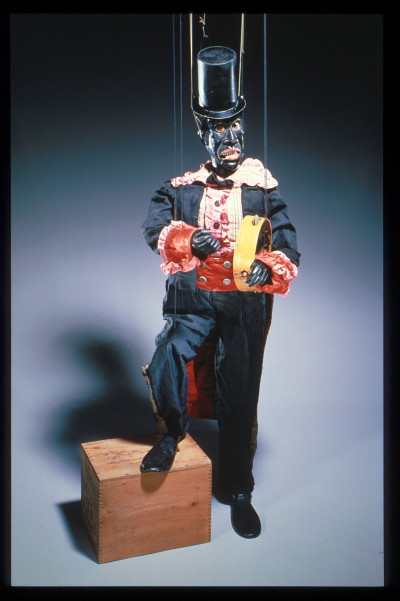

The show is performed by a troupe of 12 men including a master of ceremonies called Mr. Interlocuter and two clowns named Tambo and Bones. Male actors often played all roles, including those of women.

Upon instruction from Mr. Interlocuter, the actors would sit in a semi-circular arrangement.

A standard convention of the minstrel show was “blackface,” where Caucasian actors would paint their faces black using burnt cork to play the role of African Americans, as well as exaggerating facial features such as lips. However, after the Civil War, African Americans also began to apply the burnt cork to their faces and perform in the minstrelsy.

To learn more why Kander & Ebb chose a minstrel show as a framing device, or way to tell the story of the Scottsboro Boys, click here.

A brief history of the Minstrel show

The minstrel show emerged from many disparate, yet distinctly American sources. It is multi-racial, black and white; multi-ethnic, Jewish, Irish, Italian, African, etc; and aesthetically wide ranging. The American minstrelsy borrows from opera, English farce, Shakespeare’s plays, and Irish jigs. It also borrows from such African American forms as the juba, the knock Jim Crow (a children’s game), the ring shout (sacred ritual), and the cakewalk.

Caucasian actors had been portraying African Americans for years, but the minstrel show gained popularity when Thomas Dartmouth Rice began performing in 1830. Rice would dress in blackface and perform a song-and-dance number called “Jump Jim Crow.” Eventually, the form grew to include a group of actors rather than a soloist. One of the first was the Virginia Minstrels, who became the first blackface troupe to play New York in 1843. During this period, through the influence of the Virginia Minstrels, minstrelsy began to add skewed conceptions of plantation slave life, which ultimately translated into a negative “negro” stereotype.

Mr. Tambo marionette, courtesy of Division of Culture & the Arts, National Museum of American History, Behring Center, Smithsonian Institution.

The show further developed with E.P. Christy in 1846. Christy gave the show a three-part structure. The three parts included: Part One, the Olio, and Part Three. The show also popularized the semi-circular seating arrangement, the use of clowns Mr. Tambo and Mr. Bones and the master of ceremonies Mr. Interlocutor. The Olio portion of the show delivered the most offensive stereotypes, depicting African Americans as eating watermelons, stealing chickens, butchering language, and the worst of all, the “negro wench character” who was foul tempered and often attacked her husband with a skillet.

The minstrel show declined in popularity after the Civil War. By then, African Americans also began to perform in the shows, even creating entire troupes. They also applied the burnt cork to their face, creating their own “blackface” which had become a standard convention of the minstrel stage. For African Americans, however, painting their face was a form of “masking,” a tradition brought over from Africa from African masking rituals called “masquerades.” By blackening their faces and “performing color,” African American minstrels were able to conceal their true identities while honing their craft as artists and serving their communities by becoming cultural ambassadors and building charitable organizations.

Special thanks to Sybil R. Williams, playwright, dramaturg, and Professorial Lecturer at American University; many thanks also to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History for providing images.