A Miscarriage of Justice: The True Story of the Scottsboro Boys

“I knew if a white woman accused a black man of rape, he was as good as dead… All I could think was I was going to die for something that I had not done.”

– Clarence Norris

It all began on a train from Chattanooga, Tennessee to Memphis by way of Alabama on March 25, 1931. A white foot stepped on Haywood Patterson’s hand. He shrugged it off, but the harassment continued, and led to a fight between the white and black youths on the train. It was the early years of the Depression and all were hoboing. After they were thrown off the train, the white boys complained to a stationmaster. When the train stopped in Paint Rock, Alabama, there was a posse waiting. The sheriff’s deputies pulled off nine young African American teenagers and two white women dressed in overalls. It isn’t clear who said the word rape, but as soon as it was mentioned, the boys were arrested and brought to the nearest jail – Scottsboro, Alabama.

That was just the beginning.

A lynch mob gathered outside the jail and threatened to break down the doors. The sheriff called the governor and the governor deployed the National Guard to disperse the mob. Twelve days later the nine teenagers were put on trial.

“The courtroom was one big, smiling white face.”

– Haywood Patterson

The first trials of the boys were completed in four days. The youths received no competent counsel. They were represented by Stephen Roddy, a lawyer from Tennessee who was there at the request of friends of the boys’ parents (and unfamiliar with Alabama law) and the public defender, Milo Moody, a 69-year-old lawyer who hadn’t practiced in years. Neither lawyer was given time to prepare for the case. After swift trials, with outrageous testimony from the accusers, Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, the eight oldest were sentenced to death by electric chair and scheduled to die on July 10, 1931. Roy Wright’s trial ended in a mistrial, not because he was assumed innocent, but because due to his young age the jury could not decide whether the sentence should be death or life imprisonment.

“Why I am sitting down, thinking of no one but you, mama. They didn’t give me a fair trial. They are going to kill us for nothing.”

– Andy Wright

Applause greeted each verdict in the courtroom. Most Southern papers celebrated the verdict. But a small Communist paper phoned their main newsroom up north, drawing the attention of the Communist Party. Their legal division, the International Labor Defense (ILD), approached the boys’ parents to convince them to allow the ILD to represent the youths in the appeals. The boys and their families agreed and George Chamlee was hired by the ILD to represent them. On March 24, 1932 the Alabama Supreme Court upheld the convictions with the sole exception of Eugene Williams, due to his age. In May 1932, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the appeal.

“Do all you can to save me from being put to death for nothing. Mother, do what you can to save your son.”

– Haywood Patterson

On November 7, 1932, in Powell v. Alabama, the Supreme Court overturned the Scottsboro convictions by a vote of 7 to 2. The majority opinion determined that the defendants were denied a fair trial due to ineffective counsel who had no time to prepare, resulting in a violation of the due process clause in the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court ordered new trials. It was the first time the Court had reversed a state criminal conviction in violation for a criminal procedural provision in the Bill of Rights and set a legal precedent to guarantee defendants access to adequate council.

For the retrials, local lawyer George Chamlee succeeded in moving the trials away from Scottsboro to Decatur, Alabama. Samuel Leibowitz, one of the best criminal defense attorneys in the country, was retained by the ILD in January 1933 to lead the defense. He was a celebrated New York lawyer who had never lost a murder case. He was not a Communist and took the case pro bono. The Attorney General of Alabama, Thomas E. Knight, Jr, led the prosecution. His grandfather had been a Civil War general and his father was the Alabama Supreme Court judge who wrote the majority opinion to uphold the Scottsboro Boys’ original conviction.

“Getting out is the main thing I think about. We’re in here because of lies.”

– Eugene Williams

After Leibowitz noted there were no African Americans on the jury rolls, Haywood Patterson’s second trial began on April 3, 1933 under Judge James E. Horton, Jr. Lynch mobs gathered and again the National Guard was called.

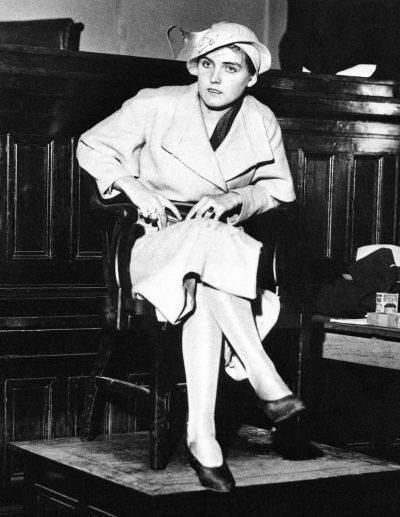

Ruby Bates testifies for the defense.

Ruby Bates was a surprise witness who came in to testify for the defense that she had not been raped by the defendants. The prosecution attacked her credibility by revealing that her clothes had been bought by the Communist Party, thus implying that her testimony had been bought as well. The prosecution also painted Leibowitz as an untrustworthy outsider because of his Jewish faith and northern roots. Despite a lack of evidence, a smiling jury voted unanimously for death.

In a seventeen-page decision, Judge Horton postponed the rest of the trials until he could determine that a fair and impartial trial was possible. He ordered a new trial for Haywood Patterson, which was a controversial move; when Horton ran for re-election in 1934, he was soundly defeated.

A new judge, William Callahan, was announced for Haywood’s retrial. The 77-year-old had never attended law school. He refused all of the defense’s requests, sustained all of the prosecution’s objections and struck from the record any testimony that did not fit his narrative. The jury again gave a guilty verdict with punishment of death. Clarence Norris’s trial ended the same way. Their executions were stayed by the Supreme Court.

“Just stuck here in the same old cell at 4:30am…If there is a god as they say he knows I am not guilty of such a hideous crime.”

– Roy Wright

On April 1, 1935, four years after the Scottsboro boys’ arrest, the Supreme Court decided two cases related to the Scottsboro trials: Norris v. Alabama and Patterson v. Alabama. In the Norris case, Leibowitz argued that the trials were inherently biased due to the exclusion of African Americans on the juries. The Supreme Court agreed that Clarence Norris had been denied his right to equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment, setting a new precedent and chipping away at Jim Crow segregation. New trials were ordered while the boys continued to languish in prison, often in solitary confinement and terrible conditions.

The all-white jury with a replica of the train, built by attorney Samuel Leibowitz.

In December 1935, the ILD, the NAACP and the ACLU came to an agreement to work together and formed the Scottsboro Defense Committee headed by Allan Knight Chalmers, a pastor from New York. Knowing that Leibowitz was now a liability to a prejudiced jury, the Committee and Leibowitz agreed that he would not lead the defense and would quietly advise Clarence Watts, a local attorney brought on to argue the case.

“If I don’t get free I just rather they give me the electric chair and be dead out of my misery because I sure don’t want no time for something I haven’t did.”

– Willie Roberson

Haywood Patterson’s new trial began in January 1936. African Americans were now required to be on the jury rolls, but now-Lieutenant Governor Knight immediately struck all from serving and Judge Callahan refused to even let the prospective black jurors take seats in the jury box. The all-white jury then heard a case very similar to the first three, with Judge Callahan allowing every prosecution objection and cutting off all testimony for the defense. The jury returned another guilty verdict, but this time recommended 75 years in prison instead of death because one juror was adamantly against the death penalty.

“I done give up. I feel like everybody in Alabama is down on me and is mad with me.”

– Ozie Powell

On the way back to jail from Patterson’s verdict, Ozie Powell, who had been suffering from mental illness due to years in confinement, attacked a guard with a small knife he had hidden on him. The guard had insulted Leibowitz and slapped him. Ozie was shot in the head. He survived but was never the same. His memory was impaired, he had trouble speaking and hearing, and his right side was very weak. After the assault and shooting, Judge Callahan postponed the rest of the trials.

“I have been in jail over five years. And it’s a shame.”

– Olen Montgomery

“I’m young and I’m innocent of a crime. I was put in solitary confinement in January 1936 and got fresh air once out of the thirteen months and that was last Friday. Some may count it a year, but I count it thirteen months.”

– Roy Wright

While the boys had now been in prison for five years in a constant state of uncertainty, the state of Alabama found keeping them taxing, both financially and politically. Prosecutor Thomas Knight visited Samuel Leibowitz in New York and over a series of weeks came to a compromise. Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson, Eugene Williams and Roy Wright would be released immediately. Leibowitz would advise Clarence Norris, Charlie Weems, and Andy Wright to plead guilty to simple assault and their sentence would not be more than 5 years. Haywood Patterson, the only one convicted, would be released at the same time they would. Ozie would only be charged for assaulting the officer. Before the agreement could be carried out, Knight suddenly died, and Judge Callahan ordered new trials.

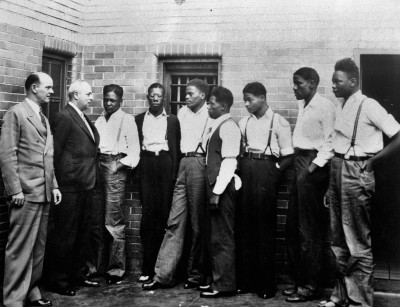

Lawyer Samuel Leibowitz with seven of the boys after asking the governor of Alabama for a pardon.

“The reason I’m in trouble is prejudice against colored people; nothing but a frame-up.”

– Charles Weems

Norris’s trial was first, beginning July 13, 1937. The trial was again fast and ended in a guilty verdict with the punishment of death. Andy Wright’s was next – guilty with 99 years. Charlie Weems got 75 years. Ozie Powell got 20 years for assaulting the deputy after rape charges against him were dropped. Then, in front of an empty courtroom, charges for the other four were dropped.

The four freed boys, Willie Roberson, Olen Montgomery, Eugene Williams and Roy Wright were taken by Samuel Leibowitz to New York. Montgomery and Wright went on a speaking tour on behalf of the five still in prison. Williams went to St. Louis where he had family and Roberson took a job in New York City. He later moved to Brooklyn, where he died of an asthma attack. Olen Montgomery attended music school, but was unable to support himself and moved from job to job. Roy Wright finished school, served in the army and got married. In 1959, convinced his wife had been unfaithful, Wright shot her and himself.

The other five, now sentenced, were transferred to a prison where they had to work twelve hours a day in cotton mills and were subjected to beatings by guards and threats of murder from other prisoners. Their health was permanently damaged.

“I have got tired of waiting. I have lost my health and my mind.”

– Andy Wright

“If anyone thinks that I am going to say I’m guilty when I am not and tell a lie on myself or anyone else, he’s crazy. If that’s the way I will have to get out of prison, I will always be here.”

– Haywood Patterson

After losing all appeals and once the Supreme Court denied to hear the case again, Scottsboro Defense Committee leader Chalmers had a protracted negotiation with the Alabama governor for pardons for the other five. Instead, the Governor commuted Norris’ sentence to life in prison. Even President Roosevelt asked Governor Bibb Graves to pardon the boys. He refused and left office at the end of his term.

Charlie Weems was finally paroled in November 1943, after 12 years in prison. Andy Wright and Clarence Norris were paroled in January 1944, Powell in June 1946.

“Everywhere I go, it seems like Scottsboro is throwed up in my face…I don’t believe I’ll ever live it down.”

– Andy Wright

After parole, Wright and Norris were made to work in a sawmill by their parole officer. It was miserable; they couldn’t make ends meet and eventually violated parole by leaving Montgomery, Alabama. Chalmers was still negotiating for Powell and Patterson’s release, and their parole violation made this task more difficult. He persuaded Norris to return to Alabama, where he was put back in prison for another two years.

Once released again he broke parole and went north, vowing never to return. Wright was in and out of prison several times during his parole, when he had trouble finding work because of his notoriety. He was finally released for good in 1950, nearly twenty years after his first night in prison. Nothing is known of his life afterward.

“This place is killing me. I don’t see why we innocent boys should be kept here all this time for nothing.”

– Haywood Patterson

Haywood Patterson was never paroled – he escaped prison in 1948 and moved to Michigan. He lived as a fugitive and quit jobs as soon as people figured out who he was. He met Earl Conrad, author of Jim Crow America, and together they published Scottsboro Boy, Patterson’s story in his own words. Alabama was furious at the book’s publishing and demanded Patterson be returned, but Michigan refused to extradite him. He was later arrested for murder in a barroom brawl, convicted of manslaughter and returned to jail. He died less than a year later from cancer at the age of thirty-nine.

Clarence Norris lived as a fugitive in New York after breaking parole. By the late 1960s, tired of the constant fear that the FBI would find him, Norris contacted the NAACP to help him arrange a pardon. After failing to convince Alabama officials to pardon Norris, the NAACP launched a public campaign in the fall of 1976. It worked. On October 25, 1976 Alabama Governor George Wallace granted Clarence Norris a full pardon. He was officially free. After publishing an autobiography, The Last of the Scottsboro Boys, Norris died in 1989, the last surviving Scottsboro Boy. He was seventy-six.

In 2013, Alabama posthumously pardoned the other Scottsboro Boys: Ozie Powell, Andy Wright and Haywood Patterson.