Censorship

- Moral Censorship: The removal of materials that are obscene or otherwise considered morally questionable.

- Military Censorship: The process of keeping military intelligence and tactics confidential and away from the enemy.

- Political Censorship: The decision by governments to withhold information from their citizens.

- Religious Censorship: The means by which any material considered objectionable by a religious group or organization is removed.

- Corporate Censorship: The process by which editors in corporate media outlets intervene to disrupt the publishing of information that portrays their business or business partners in a negative light.

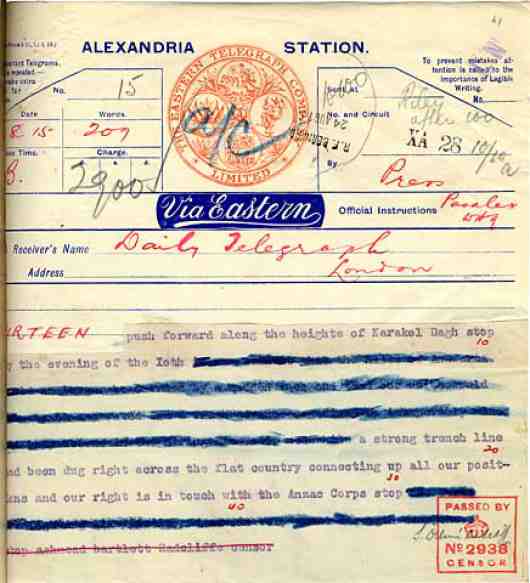

A censored telegram with sensitive information blacked out.

Throughout history, societies have practiced various forms of censorship in the belief that the community, as represented by the government, is responsible for molding the individual. For example, the ancient Greek philosopher Plato advocated various degrees of censorship in The Republic, believing that to have a good society we must promote good material and suppress bad material. The content of important texts and the spreading of knowledge were tightly controlled in ancient Chinese society (as is much information in modern China). For centuries, the Roman Catholic Church’s List of Prohibited Books proscribed much literature as contrary to the church’s teachings.

The Republic‘s overall argument for censorship combines a particular idea of morality with authoritarian politics. The argument is as follows:

- To have a good society, we must have good citizens.

- To have good citizens, children must be well educated.

- To be well educated, children must be exposed to good material and shielded from bad material.

- So, to have a good society, children must be exposed to good material and shielded from bad material.

- It is the obligation of the State to educate its citizens.

- So, the State should allow only good material and suppress bad material.

- The State’s censorship applies also to art.

- So, the State should allow only good art and suppress bad art.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulates media content in the United States today, and its decisions and policies have been challenged many times in the last century. Books often run into issues with censorship, particularly in regards to younger readers. One of the most obvious places where book censorship comes into play are public schools. Conflict ensues when parents believe that certain school books contain material that is objectionable and should be banned in order to protect their children from exposure to allegedly harmful ideas. Remember that for people, censorship is intended to protect younger minds from materials that they may not be ready for as well as making sure the content is strong and useful. In some instances, school boards have responded by physically removing books from school library shelves. In general, advocates of book banning maintain that censorship is warranted to redress social ills, whereas critics believe that freedom of speech is more important and useful to society than imposing values through censorship.

Book banning as a way to remedy social problems was first tested by the Supreme Court in Board of Education v. Pico (1982). In this case, parents objected to eleven books in the high school library, most of which were subsequently removed by the school board. The nine books included Slaughterhouse Five, by Kurt Vonnegut Jr.; Naked Ape, by Desmond Morris; Down These Mean Streets, by Piri Thomas, and Best Short Stories of Negro Writers, edited by Langston Hughes.

High school senior Steven Pico brought the case to debate the authority of local school boards to censor material in the interest of protecting students. The case reached the Supreme Court, which ruled that it is unconstitutional for public school boards to abridge students’ First Amendment rights by banning books. Although school boards have the power to determine which books should sit on library shelves, they do not have the authority to censor what students read on their own time.

Section Objective: Through discussion and theatrical exercises, students will explore reasons for censorship, articulating what they feel are good and bad reasons for silencing or banning certain messages or presentations. In exploring what has been censored, they’ll also be invited to explore the worth of the media they consume and the positive impacts it has had on their lives.

Discussion Questions:

- Is censorship always a bad thing? When may it be helpful?

- Have you read any books that you have interpreted as “controversial?”

- Have you ever gone to a theatre performance that had signs warning you of violent or graphic content? Have you ever gone to a performance that did not issue warnings but made you uncomfortable based on the content? Do you wish some of that content was censored?

- How has the evolution of media and literacy affected our attitudes toward censorship and ability to access controversial material?

Citations / Further Exploration:

The Long History of Censorship: http://www.beaconforfreedom.org/liste.html?tid=415&art_id=475

What is Censorship?: https://ncac.org/resource/what-is-censorship

On Censorship: https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/on-censorship

Censorship Defintion: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/censorship

Exercise: The Censor Has Spoken

Subject(s): English, Theatre, History

Goals:

Students will be able to:

- identify and summarize essential details that support the main idea of informational text.

- analyze, compare, and contrast multiple texts for content, intent, impact, and effectiveness.

- promote collaboration with others both inside and outside the classroom.

- explore the ethical and legal issues related to the access and use of information.

- apply civic virtues and democratic principles to make collaborative decisions.

Supplies: Paper, pencils, book excerpts

Discussion:

- How would you define “censorship”? Have you been censored before?

- the suppression or prohibition of any parts of books, films, news, etc. that are considered obscene, politically unacceptable, or a threat to security.

- Why do people censor things and people?

- What is the benefit or cost of censorship?

Set Up:

Students are divided up into groups.

- Each group is assigned a small excerpt from a banned or challenged text. (We used the following but feel free to choose books and excerpts that fit the needs of your students: Of Mice and Men, Catcher in the Rye, 1984, The Giver)

- These excerpts should highlight the dangerous or upsetting quality that is often referenced when nominating it for banning.

- Each group is to read their assigned excerpt of “bannable” content and discuss why it may be seen as worthy of censorship. In their small groups, they discussed with their teachers why each piece could be considered “dangerous” and why each piece could be considered beneficial as well.

Discussion:

- Invite one student per quote up to read them aloud:

“If this nation is to be wise as well as strong, if we are to achieve our destiny, then we need more new ideas for more wise men reading more good books in more public libraries. These libraries should be open to all—except the censor. We must know all the facts and hear all the alternatives and listen to all the criticisms. Let us welcome controversial books and controversial authors. For the Bill of Rights is the guardian of our security as well as our liberty.” – John F. Kennedy

“Something will be offensive to someone in every book, so you’ve got to fight it.” ― Judy Blume

“Having the freedom to read and the freedom to choose is one of the best gifts my parents ever gave me.” ― Judy Blume

“Yet when books are run out of school classrooms and even out of school libraries as a result of this idea, I’m never much disturbed not as a citizen, not as a writer, not even as a schoolteacher . . . which I used to be. What I tell kids is, Don’t get mad, get even. Don’t spend time waving signs or carrying petitions around the neighborhood. Instead, run, don’t walk, to the nearest non-school library or to the local bookstore and get whatever it was that they banned. Read whatever they’re trying to keep out of your eyes and your brain, because that’s exactly what you need to know.” ― Stephen King

“Censors don’t want children exposed to ideas different from their own. If every individual with an agenda had his/her way, the shelves in the school library would be close to empty.” ― Judy Blume

“Where they burn books, they will, in the end, burn human beings too.” – Christian Johann Heinrich Heine

- Once this has been completed, invite them to think about the songs, albums, books, movies, plays they love – banned or not. Why do you love it?

- Instruct students to write the following in large letters on several sheets of blank paper. “Please don’t ban ____________. It ________________” (We also have prepared worksheets for this exercise. If you’d like a PDF version of them, send a request to education@sigtheatre.org.)

- Students then fill in the first line on their sheets with media titles or artists’ names. Media and artists they love. In the second line, they should articulate why that media or artist matters, essentially arguing for its worth. (“Please don’t ban the new Ghostbusters. It means a lot to me to see women in these roles in this kind of movie,” etc.) The things they choose don’t have to be inherently controversial. This is a celebration of the worth of books, movies, songs, plays, albums, artists. Not a celebration of the power of censorship.

Exercise: Censored Cases

Subject(s): English, Theatre, History

Goals:

Students will be able to:

- apply narrative techniques, such as dialogue, description, and pacing to develop experiences or characters.

- develop the topic with appropriate information, details, and examples.

- promote collaboration with others both inside and outside the classroom.

- evaluate the evolving and changing role of government.

Supplies: Computer, internet access, case background information

Set Up:

- Students are placed into separate groups and are directed to the internet to research court cases that highlight a particular form of censorship.

- Each group takes 20 minutes to brainstorm and prep a presentation on the case / subject matter / ruling. Pieces must be four vignettes taking us through the arc of the case and circumstances. One or multiple members of the group should serve as a narrator. Other members of the group can speak up in the vignettes to flesh out extra details. Each member of the team must be involved in the presentation somehow. Groups should feel free to use any and all supplies they wish.

Group 1: West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943).

Group 2: Tinker v. Des Moines, 393 U.S. 503 (1969)

Group 3: Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989)

Group 4: United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968)

Group 5: Bethel School District #43 v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675 (1986)

West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943).

- In 1942, the West Virginia Board of Education required public schools to include salutes to the flag by teachers and students as a mandatory part of school activities. The children in a family of Jehovah’s Witnesses refused to perform the salute and were sent home from school for non-compliance. They were also threatened with reform schools used for criminally active children, and their parents faced prosecutions for causing juvenile delinquency.

- The main question: Did the compulsory flag-salute for public schoolchildren violate the First Amendment?

- The answer: In a 6-to-3 decision, the Court overruled its decision in Minersville School District v. Gobitis and held that compelling public schoolchildren to salute the flag was unconstitutional. In an opinion written by Robert Houghwout Jackson, the Court found that the First Amendment cannot enforce a unanimity of opinion on any topic, and national symbols like the flag should not receive a level of deference that overrides constitutional protections. He argued that curtailing or eliminating dissent was an improper and ineffective way of generating unity.

Tinker v. Des Moines, 393 U.S. 503 (1969).

- In December 1965, a group of students in Des Moines held a meeting in the home of 16-year-old Christopher Eckhardt to plan a public showing of their support for a truce in the Vietnam war. They decided to wear black armbands throughout the holiday season and to fast on December 16 and New Year’s Eve. The principals of the Des Moines school learned of the plan and met on December 14 to create a policy that stated that any student wearing an armband would be asked to remove it, with refusal to do so resulting in suspension. On December 16, Mary Beth Tinker and Christopher Eckhardt wore their armbands to school and were sent home. The following day, John Tinker did the same with the same result. The students did not return to school until after New Year’s Day, the planned end of the protest. Through their parents, the students sued the school district for violating the students’ right of expression and sought an injunction to prevent the school district from disciplining the students. The district court dismissed the case and held that the school district’s actions were reasonable to uphold school discipline. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit affirmed the decision without opinion.

- The main question: Does a prohibition against the wearing of armbands in public school, as a form of symbolic protest, violate the students’ freedom of speech protections guaranteed by the First Amendment?

- The answer: Yes. The Supreme Court held that the armbands represented pure speech that is entirely separate from the actions or conduct of those participating in it. The Court also held that the students did not lose their First Amendment rights to freedom of speech when they stepped onto school property. In order to justify the suppression of speech, the school officials must be able to prove that the conduct in question would “materially and substantially interfere” with the operation of the school. In this case, the school district’s actions evidently stemmed from a fear of possible disruption rather than any actual interference.

Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989).

- In 1984, in front of the Dallas City Hall, Gregory Lee Johnson burned an American flag as a means of protest against Reagan administration policies. Johnson was tried and convicted under a Texas law outlawing flag desecration. He was sentenced to one year in jail and assessed a $2,000 fine. After the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reversed the conviction, the case went to the Supreme Court.

- The main question: Is the desecration of an American flag, by burning or otherwise, a form of speech that is protected under the First Amendment?

- The answer: In a 5-to-4 decision, the Court held that Johnson’s burning of a flag was protected expression under the First Amendment. The Court found that Johnson’s actions fell into the category of expressive conduct and had a distinctively political nature. The fact that an audience takes offense to certain ideas or expression, the Court found, does not justify prohibitions of speech. The Court also held that state officials did not have the authority to designate symbols to be used to communicate only limited sets of messages, noting that “if there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the Government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.”

United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968).

- David O’Brien burned his draft card at a Boston courthouse. He said he was expressing his opposition to war. He was convicted under a federal law that made the destruction or mutilation of draft cards a crime.

- The main question: Was the law an unconstitutional infringement of O’Brien’s freedom of speech?

- The answer: No. The 7-to-1 majority, speaking through Chief Justice Earl Warren, established a test to determine whether governmental regulation involving symbolic speech was justified. The formula examines whether the regulation is unrelated to content and narrowly tailored to achieve the government’s interest. “We think it clear,” wrote Warren, “that a government regulation is sufficiently justified if it is within the constitutional power of the Government; if it furthers an important or substantial governmental interest; if the governmental interest is unrelated to the suppression of free expression; and if the incidental restriction on alleged First Amendment freedoms is not greater than is essential to the furtherance of that interest.”

Bethel School District #43 v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675 (1986).

- At a school assembly of approximately 600 high school students, Matthew Fraser made a speech nominating a fellow student for elective office. In his speech, Fraser used what some observers believed was a graphic sexual metaphor to promote the candidacy of his friend. As part of its disciplinary code, Bethel High School enforced a rule prohibiting conduct which “substantially interferes with the educational process . . . including the use of obscene, profane language or gestures.” Fraser was suspended from school for two days.

- The main question: Does the First Amendment prevent a school district from disciplining a high school student for giving a lewd speech at a high school assembly?

- The answer: No. The Court found that it was appropriate for the school to prohibit the use of vulgar and offensive language. Chief Justice Burger distinguished between political speech which the Court previously had protected in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) and the supposed sexual content of Fraser’s message at the assembly. Burger concluded that the First Amendment did not prohibit schools from prohibiting vulgar and lewd speech since such discourse was inconsistent with the “fundamental values of public school education.”

Exercise: Expression Booth

Subject(s): English, Theatre

Goals:

Students will be able to:

- use examples from their knowledge and experience to support the main ideas of their oral presentation.

- use grammar and vocabulary appropriate for situation, audience, topic, and purpose.

- demonstrate nonverbal techniques including, but not limited, to eye contact, facial expressions, gestures, and stance.

- use verbal techniques including, but not limited to, appropriate tone, diction, articulation, clarity, type, and rate.

- keep eye contact with audience, adjust volume, tone, and rate, be aware of postures and gestures, use natural tone.

Supplies: Table, chairs, and whatever students elect to bring.

Set Up:

- Part one: The homework assignment. Every student will create a “booth” (interactive, presentational or otherwise) on a subject they would like to express to a portion of the class. These expression booths can feature items from your life, favorite things, an exploration of an aspect of your identity / personality. Every student’s “booth” must feature at least two items that relate to your subject in some manner. These booths will be presented the next time the class meets. (This allows students some prep time at home.)

- Part two: The classroom. Half of the group will set up and present their booths at a time while the other half of the group interacts with the booths and gets a chance to explore them. Groups will switch later. When presenting their booth students are highly encouraged to be as invested in your given moment or topic of expression. This is their time and space to share whatever it is they want to share.

- Once everyone in the first presenting group is ready to present, open it up for 5-10 minutes of exploration from booth to booth.

- Note for instructors: While walking through the booths, take notes on how you could censor each person’s booth. (“You must remove any reference to___________,” “Please replace the following things [ ] with [ ],” “Your booth is inflammatory and offensive. Please remove all materials and take a seat.” Do not censor them yet. Just take notes for censoring later.

- Once students have taken a look at all of the booths, swap out and have the next group set up.

- Once the group is ready to present, open for 5-10 minutes of exploration from booth to booth. Instructors repeat their process from the previous round.

- Bring full class together to discuss things they appreciated, observed and learned.

- Instruct the students from the first presenting group to set up their booths one more time. Explain that this time, however, you found some things to be inappropriate for this setting. Offensive even. So, you are going to give each of them some notes. (Proceed to make adjustments.) Once you’ve gotten your notes, you may begin to reset your booth.

- As a time-saving mechanism, you may want only the students who were given notes to present this time. If you gave notes to everyone, follow the pattern from before with half the group presenting while the other observes, followed by a reversal.

- Discuss pieces. How did it feel to have to change your plan / expression? Did you fight against this?