Patriotism at the Beginning of the 20th Century

“A nation without patriots cannot long endure.” – Manual of Patriotism, 1900. Published by the New York State Department of Schools.

The dawn of the 20th Century saw America in a period of dramatic growth in all aspects: economically, technologically, and militarily. America was on the brink of being a world power for the first time in its history. In turn, this led to a dramatic rise in American patriotism and national pride – to the extreme of jingoism – a fanatical, over-the-top patriotism. This form of heightened nationalism contributed to an aggressive foreign policy and an undiscerning allegiance to all things American. Furthermore, it defined “American” by a narrow set of parameters – those that were white, straight, male, conservative, and Christian.

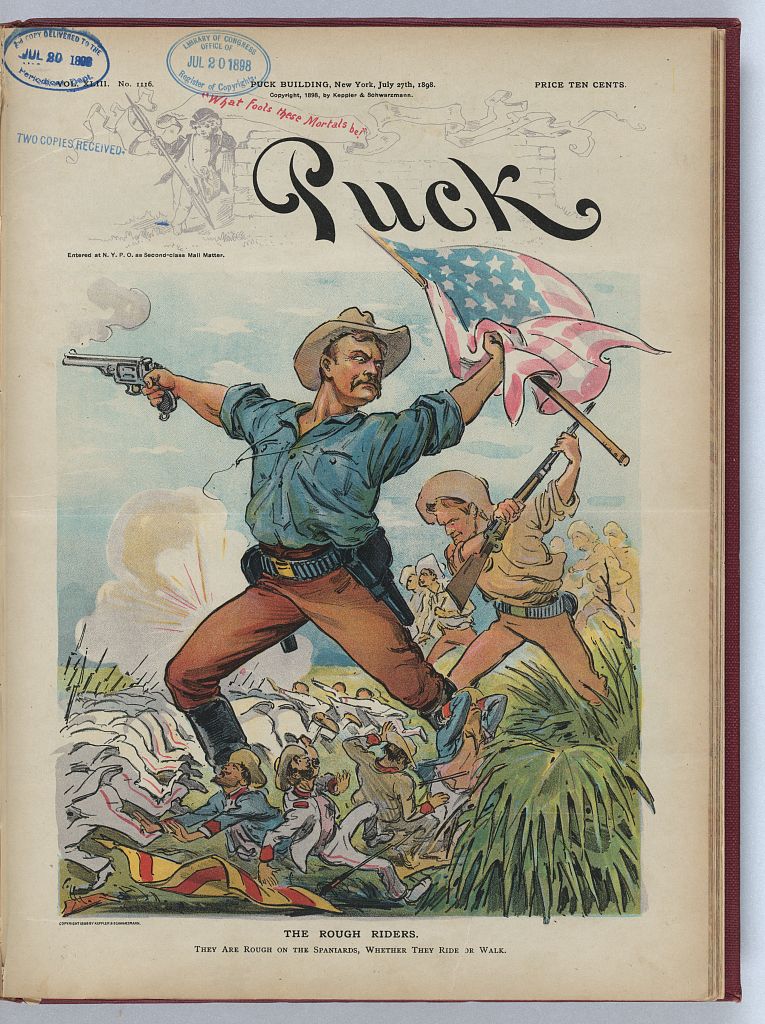

Depiction of Roosevelt and San Juan Hill from Puck Magazine

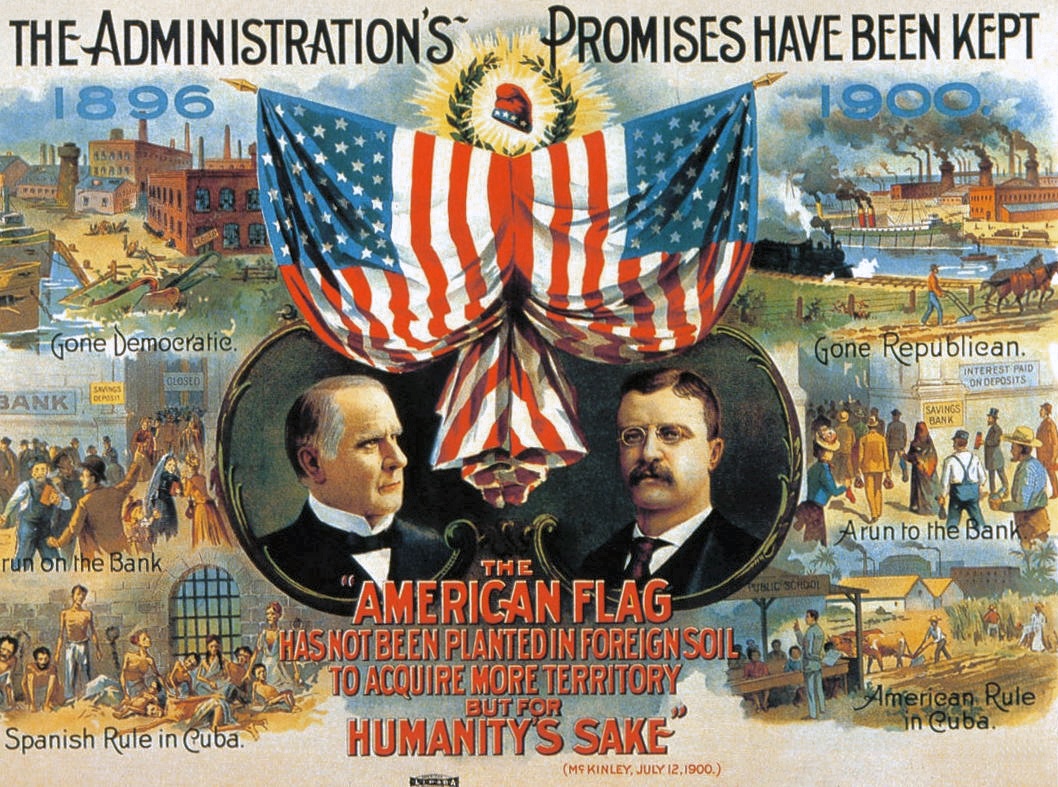

In the late 1800s, America was achieving military victories across the continent and abroad. The division of The Civil War was fading from living memory – President McKinley, elected in 1896 and 1900, was the last Civil War president. Instead, Americans from the North and South were fighting on the same side against common foes. America’s success in the Spanish-American War in 1898 demonstrated that America was beginning to step onto the world stage and flex its muscles as a new power. The conflict only lasted 100 days and was a triumphant victory over Spain. With Spain’s expulsion, the United States was now the sole power in the Western Hemisphere. Its hero, Theodore Roosevelt, would ascend to the presidency following McKinley’s assassination, and also be later elected in his own right. Not just content with success on the continent, the United States began imperialist annexes, taking the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Guam, and later Hawaii. They forced diplomatic relations with Japan. There was a feeling of superiority over the non-white population.

William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Campaign Poser 1900

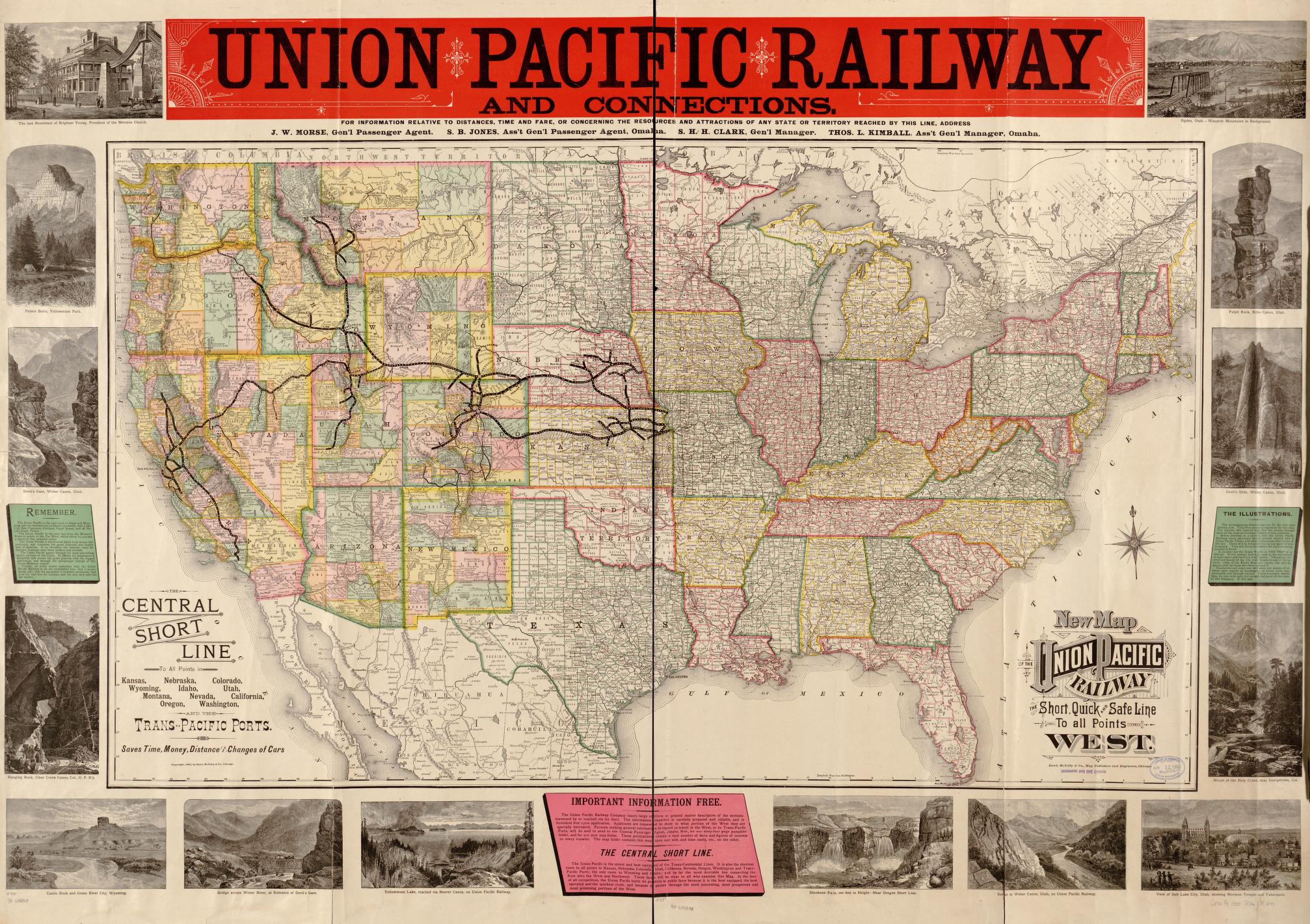

Meanwhile, the country was enjoying a boost of economic growth from the Industrial Revolution. America benefitted from the advancement in technology and entrepreneurialism far more than the rest of the globe. In rapid succession there were gasoline cars, telephones, skyscrapers, home electricity, radio, and movies. The transcontinental railroad had spread from coast to coast, and by 1900 there were 193,000 miles of track and five railroad systems. The country’s infrastructure had been dramatically altered in the span of one person’s lifetime as people flooded into cities. While most of the gains went to the few at the top, there was still an optimistic feeling about the future. Anything was possible – and that America would be at the forefront of invention.

New Railway Lines

Environmentally, Americans were exploiting the abundant natural resources of the continent they had newly dominated. By 1900 Americans had conquered the Wild West – there was no more frontier – and the United States owned all the land from coast to coast. In addition, the American government completed the destruction of the indigenous people’s sovereignty. Following Apache chief Geronimo’s surrender in 1886, all indigenous people were all now confined to reservations – and all their land and its riches were rife for the taking. Oil had been discovered, drilled, and the supply seemed limitless – John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust controlled more than 90% of the nation’s refinery capacity. Steel was being manufactured and by the turn of the century the United States was the largest steel producer in the world. America also became the largest agricultural producer in the world as they closed off the open range and transferred the land to private ownership and tilled the rich soil.

The rapid growth in all segments led to a patriotism that was unabashed and strong. However, the Americans who reaped the gains of the last fifty years were predominantly wealthy, male, Christian and white. The American nationalism at the top of the Twentieth Century was closely tied to a racial hierarchy that placed white Americans at the top. At its core, historian Gary Gerstle argues in his book American Crucible: Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century, nationalism must be about exclusion. In order for someone to belong to something, and derive pride and superiority from it, it must be at the exclusion of someone else. For instance, when Spanish American war hero Theodore Roosevelt charged up the San Juan Hill, he did so with the assistance of several Black troops. However, he later diminished their bravery by describing those troops as “peculiarly dependent on their white officers.”

Sketch of the 10th Cavalry Charge at San Juan

Author E.L. Doctorow skewers this idea of patriotism in Ragtime. The character of Father has become wealthy through the sale of fireworks and other displays of patriotism. His business is thriving, but although many of his customers are immigrants and other people of lesser means, he is the one who is benefitting. This wealth also gives the wealthy white characters a sense of superiority and the luxury to ignore the plight of other Americans. However, by the end of the story, those same fireworks are used as explosives. It’s a warning of the dangers of nationalism and exclusion.

The parallels between America at the turn of the 20th Century and America of the present also extend to the theme of patriotism and nationalism. There has been a dangerous rise in white nationalism in the past decade that is targeting those who do not fit its narrow mold. The rapid technological advances have again stratified society by allowing monopolies to corner markets. The few at the top reap the gains such as billionaires Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk. America cannot allow itself to fall down the destructive path of restricting who gets to be an American. As Ragtime demonstrates, the results can be explosive.