Harlem Transformed: The History of Harlem

While Harlem is now known as the Black Capital of the world, over the course of its 400 years of development, Harlem has been home to many people. Initially the area was inhabited by the Manhattans, along with other tribes, who occupied the land on a semi-nomadic basis. Dutch settlers arrived in 1658, named the area Nieuw Haarlem after the Dutch city of Haarlem, and for 200 years the area was farmland. As New York City grew, however, Haarlem lost it’s second “a” and development expanded upwards from Manhattan into the Harlem area.

Harlem in 1905

Beginning in the 1880s, rail lines were added northwards on 8th and 9th Avenue. The connection to downtown creating a building spree and brownstones and family apartment buildings were rapidly constructed. The primary buyers were merchants and other businessmen who moved their families north to where it was quieter and they could get more space for their money. Many of the families were Jewish, Italian or German immigrants and their descendants. In 1893, Harlem Monthly Magazine wrote that “it is evident to the most superficial observer that the centre of fashion, wealth, culture, and intelligence, must, in the near future, be found in the ancient and honorable village of Harlem.”

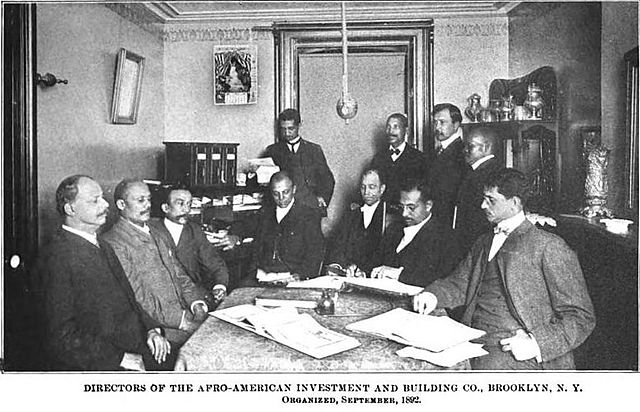

Directors of the Afro-American Investment and Building Co., 1892

Then, in 1904, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company built an underground subway station line called the IRT Line. It connected the lower side of Manhattan to 145st in Harlem. Seeing how successful development was following the rail lines, speculators quickly bought all available property around the stations and began a frenzied building boom. However, they overestimated the demand and greatly overbuilt. Blocks of new brownstones and apartments sat vacant, and developers grew desperate as the glut in housing caused a crash in value.

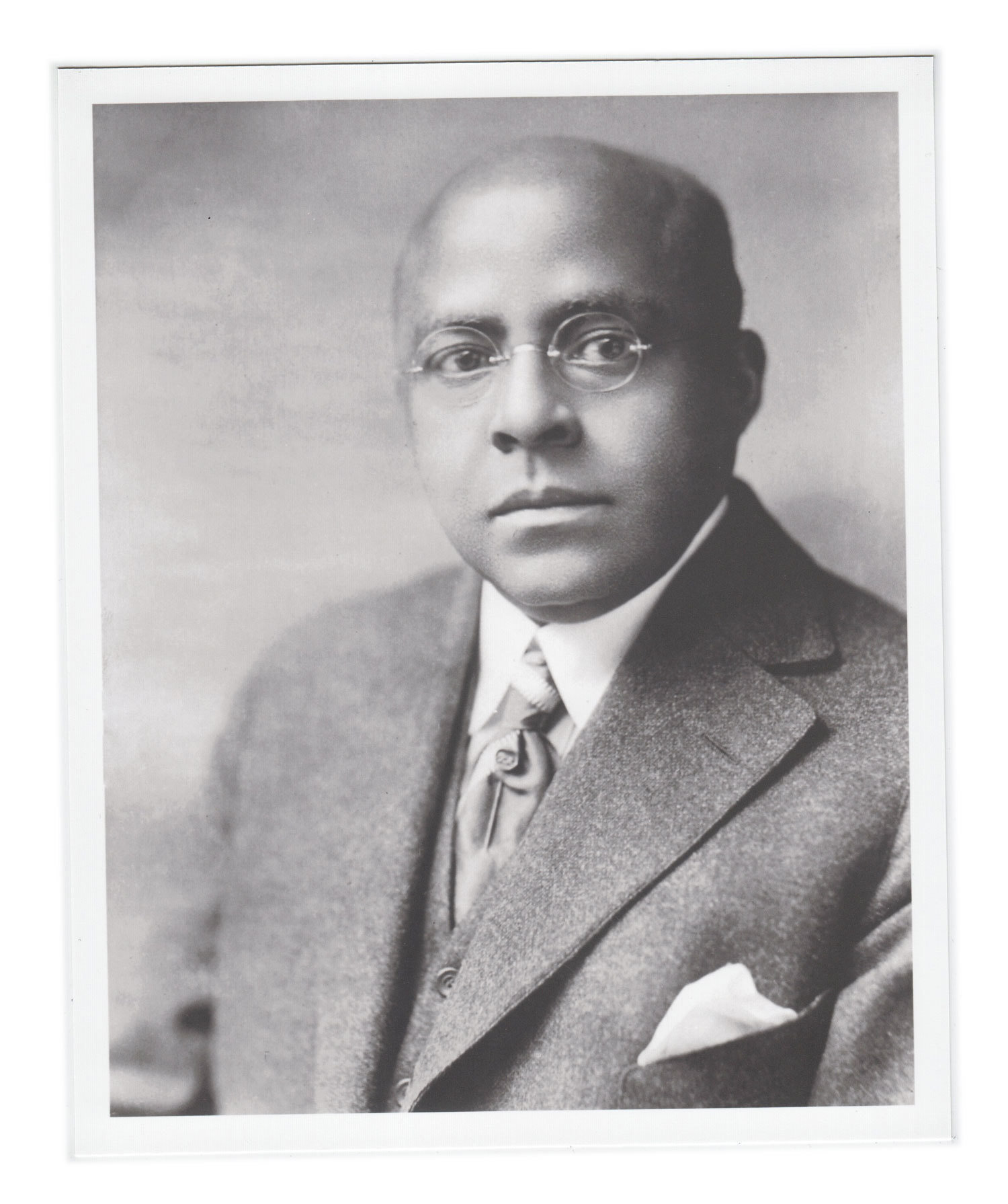

Philip A. Payton

Noting this desperation, entrepreneur Philip A. Payton, Jr. saw an opportunity. New York City had recently seen a flux in Black immigration from the rural south. The end of the Reconstruction Era and rise of Jim Crow led to thousands of Black Americans fleeing the repression of the south and seeking new economic opportunities. While exact numbers are difficult to confirm, by 1900, an estimated 335,000 southern born African Americans had moved north, mostly to cities such as New York or Philadelphia. However, they had a difficult time securing housing when white owners refused to rent to them. In lower Manhattan, people were living in squalid and crowded conditions and subject to police brutality.

Payton approached several Harlem landlords and suggested they open up their underoccupied buildings to Black paying tenants. While he initially faced resistance, he did begin managing a building on 134th street that he filled with Black tenants. The city’s Black citizens finally had access to decent housing, and they eagerly moved to Harlem. Payton achieved such success that he was able to build a real estate business that catered exclusively to the Black population called the Afro-American Realty Company. Founded in 1904, he appealed to Black investors with a prospectus declaring, “The very prejudice that has heretofore worked against us can be turned and used to our profit.”

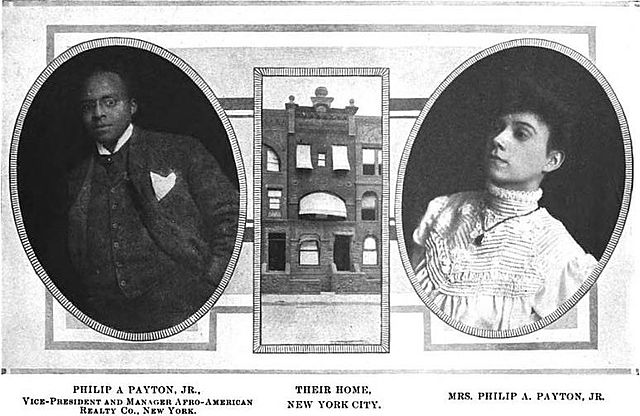

Mr. and Mrs. Philip A. Payton Jr. and their home, New York City

While the transformation was not smooth as people were met with resistance from several of the white property owners, the economic pressure of vacant buildings proved too much, and Payton’s company continued to win contracts. The company eventually moved past managing and bought two dozen buildings in Harlem. It used the buildings to exclusively house Black New Yorkers, those from the rural south, and Caribbean immigrants. They rebranded the area by naming their buildings in honor of prominent Black Americans such as Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington. Payton later created his own company, the Philip A. Payton Jr. Company to further expand, although that later collapsed. By 1913 there were 50,000 to 70,000 Black Americans living in Harlem. Sadly, Payton died just a few years later from liver cancer at the age of 41 in 1917. He did not get to see the artistic and cultural flourishment of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s that would never have possible without his initiative and ingenuity. However, his home still stands on 131st street, a monument to his lasting legacy as the “Father of Harlem.”