East Meets West

In 1853, steam engine-powered ships were a relatively new technological invention. The Japanese called these ships the “Black Ships,” either because of their painted color or because of the clouds of smoke from their coal-powered engines. As they had never seen these types of ships before, it was a terrifying sight. This image is Perry’s ship, the USS Susquehanna.

In this painting by James G. Evans, called “The US Japan Fleet, Commodore Perry carrying The Gospel of God to the Heathen, 1853,” the United States is depicted as the hero and a “savior” to the Japanese, thus assuming an air of righteousness for the invasion.

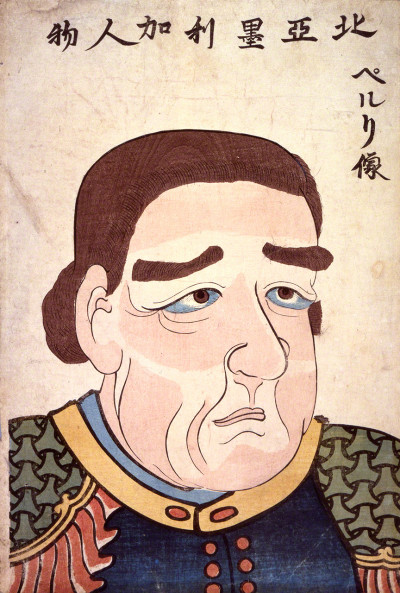

Woodblocks were a popular way Japanese artists created portraits. In this one, which is the most well-known woodblock image of Matthew Perry, called “Portrait of Perry, a North American” circa 1854, Perry’s jowls are pronounced, and he has blue eyeballs, a common way the Japanese portrayed monsters or barbarians.

Most Americans would have known Matthew Perry from a photograph rather than a piece of artwork. The daguerreotype of Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry has him in his navy uniform and was taken by famed photographer Mathew Brady in 1856. Brady had extensive experience in stylizing photographs to show subjects in a flattering light.

This gallery of individuals depicts members of Perry’s crew, from left to right; the navigator, an Infantryman, Infantry Commander, the crewman who surveys the depths, the Interpreter, and Commodore Perry himself. The prints were utilitarian rather than artistic expression. They were made and mass distributed to explain to the Japanese community who the new foreigners were.

Japanese artists were often unable to get an actual glimpse of Perry and had to rely on their imaginations or descriptions to depict the Americans. Some artists drew them as “tengu” a mythical long-nosed goblin, or as “hairy barbarians.” This image is of Matthew Perry and his second-in-command Henry A. Adams both elongates the nose and adds conspicuous hair.

Following the Kanagawa convention and the explosion of foreigners entering Japan, artist channeled their frustrations of the invasions with patriotic displays of sumo wrestlers, who were national heroes, tossing the unwelcome foreigners around. This illustration is titled “The Glory of Sumo Wrestlers at Yokohama,” circa 1860-1861

This first part of the 1854 “Black Ship Scroll,” a 30-foot-long scroll created to satisfy curious Japanese about the foreigners, maps the harbor with names and ships at various angles so that it can be viewed from several angles at once or rotated as it was read.

William Speiden, Jr. was Perry’s purser during his expedition. He kept a journal during his career of traveling and drew his own map of Japan’s coastline. He notes the other ships and writes Edo as Yedo, which was a common anglicized name for the city.

When the Americans arrived, they brought photographic equipment with them to document the Japanese people for readers back home. This lithograph with added color was made from a daguerreotype by Eliphalet Brown, Jr. of Chief Interpreter Moryamo Yenosky and Tako Juro, two men who served as interpreters in 1854.

This portrait of two women in Simoda is by Eliphalet Brown, Jr., who traveled with Matthew Perry for his second trip in 1854. As daguerreotypes were very fragile with no negative, they were replicated as lithographs with color added that allowed for mass production for American audiences.

As daguerreotypes required time and stillness, they were not appropriate for larger action documentation. For those images, artist William Heine worked with a sketchpad and watercolors. His illustrations added a romantic flourish, and, as the Americans never entered Edo or any of the larger cities, only depicted rustic scenery. Here Heine imagines Perry coming ashore first the time to deliver President Fillmore’s letter.

German artist William Heine was hired to document Perry’s expedition, and he composed images to show the Commodore as exalted with patriotic flags unfurled and being solemnly greeted by the Shogun’s representatives. The Shogun’s representative gives a deeply respectful bow that Perry does not reciprocate and he is centered in the image. Perry is also drawn as younger and fitter than he actually was at the time of the expedition.

Japanese artist Hibata Ōsuke painted a handscroll to document Perry’s second visit to Japan. It contains several images that emphasize the Japanese military might. This image depicts the Japanese hosting the American soldiers to dinner. Notably the samurai all have their weapons, and the Americans are without. The five Japanese are (from the right): Hayashi Fukusai, the chief Shogunal negotiator and head of the Confucian Academy; Ido Satohiro, Edo City Magistrate; Izawa Masayoshi, Uraga Magistrate; Udono Kyūō, Inspector General; and Matsuzaki Ryūrō, a direct retainer of the Shogun.

Click here to learn more in this visual essay by John W. Dower