Blog: The African American Women of the Wild West

Inspired by a true story, Gun & Powder depicts two African American sisters who became notorious outlaws in the Wild West. Although they're not usually the main characters in modern cowboy stories (if they're depicted at all), there were large numbers of African American men and women living in all of the Western states. The frontier expansion offered both a new way of life and economic independence that was not afforded to either African Americans or women in the East.

African American women made enormous contributions to the advancement and culture of the West. They built towns, established charities, created schools, developed churches, and did dangerous jobs such as delivering the mail. They were real estate magnates, writers, celebrated chefs, investors and trailblazers.

Below are the stories of six women and the exciting and inspiring lives they led when they went West.

Biddy Mason

Bridget “Biddy” Mason

Real Estate Magnate and Philanthropist

(1818 – 1891)

Biddy Mason was born into slavery in 1818, but her exact birthplace is unknown; like so many enslaved people, she was forcibly taken from her family and sold several times. Her final owner, Robert Smith, converted to Mormonism and moved his household, including Biddy, to California with a larger group of church members. California was a free state and Biddy was legally free as soon as she entered the state, but her owner Smith kept her from learning of her right to freedom for five years. Once she learned this, she petitioned the court for freedom for herself and her children. Despite the obstacles Smith set in place, and the fact that she was not allowed to testify, she won her family’s freedom and adopted the surname Mason.

Mason settled in Los Angeles and worked as a nurse and a midwife. After saving money for a decade, she invested in real estate, becoming one of the first Black female landowners in Los Angeles. Her wise investments made her a fortune and a prominent citizen of the city, which she used to establish multiple charities, schools, daycares and the first African American church in Los Angeles. She died in 1891 as one of the richest women in the city.

Susie Sumner Revels Cayton

Susie Sumner Revels Cayton

Writer and Editor

(1870 – 1943)

Born in 1870 in Mississippi, Susie Sumner Revels was the daughter of Reverend Hiram Revels, the first elected African American to the United States Senate. She was named in honor of family friend and prominent abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. In 1896, after graduating from college, Revels married newspaper owner Horace Cayton and moved west to join him in Seattle.

Horace Cayton had founded the Seattle Republican newspaper in 1894 and Susie regularly contributed content and served as Associate Editor. The paper appealed to both White and Black readers and eventually grew to be the second largest circulated paper in the city. The couple eventually became the only Black family to live in the affluent Capitol Hill area of Seattle. Susie Cayton was also immensely involved in civic life, she founded the Dorcus Charity Club and successfully organized boycotts for business that discriminated against African Americans. Unfortunately, as racism intensified in the city, revenue for the paper dropped and forced the Caytons to close the paper in 1913 and sell their home. She continued her passionate activism into her 60s and 70s, when she joined the Communist party. Late in her life Cayton became friends with actor/activist Paul Robeson and writer Langston Hughes, who dedicated his poem “Dear Mr. President” to her.

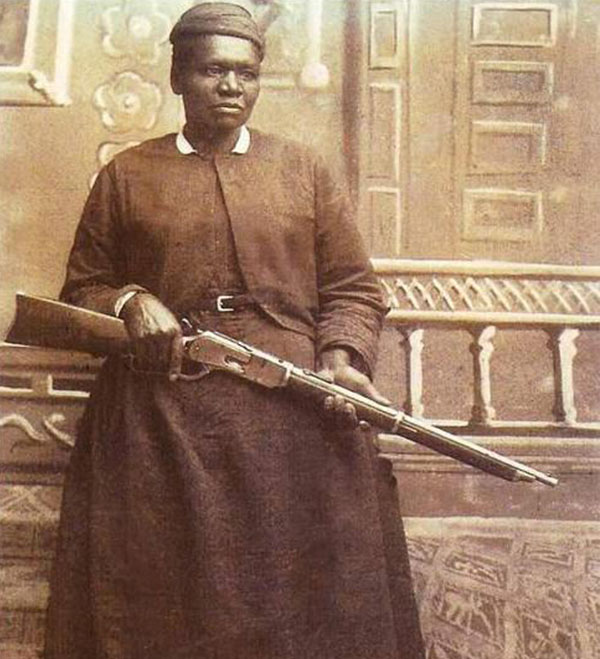

Mary Fields

Mary Fields, aka Stagecoach Mary

Trailblazer

(Circa 1832 – 1914)

Mary Fields, or Stagecoach Mary, was the first African American woman (and only the second woman overall) to be a star route mail carrier in the United States. Born into slavery in Tennessee around 1832, she received her freedom at the end of the Civil War. After working on a variety of jobs, Mary took employment with a convent in Toledo. She grew very close to one nun, Sister Amadeus, and was saddened when the nun left for a Jesuit mission in Montana. When Sister Amadeus contracted pneumonia, Mary Fields rushed to Montana to care for her and stayed for ten years with the mission. She started out doing general repairs, laundry, and other types of manual labor and worked her way up to become the forewoman. Standing at 6’ and around 200lbs, Mary was an imposing figure and would not tolerate disrespect from anyone. She was forced to leave the convent after tensions boiled over and led to a brawl with another worker on her team.

In 1895, she became the second female mail carrier in the country. She was then in her sixties. Mary earned the nickname Stagecoach Mary for her reliability and bravery through all conditions of what was a very dangerous job. After she retired from her star route contract, Mary settled in Cascade as its only African American resident. She was well known and popular in her city for her accurate shot, her cigar, her whisky, her kindness, and her charity. Mary was the exception to rules and social norms in Cascade: when a law was passed barring women from saloons, the mayor granted Mary an exception and, as she didn’t know her birthdate, the town celebrated her birthday twice a year.

Elizabeth Thorn Scott Flood

Elizabeth Thorn Scott Flood

Educator and Activist

(1828 – 1867)

Elizabeth Thorn was born free in 1828 in New York state and she was educated in Massachusetts. She married Joseph Scott in 1852 and they moved to northern California later that year. After Joseph died, Elizabeth and their son Oliver moved to Sacramento. At the time, Sacramento had a sizable African American community, but because all non-white children were barred from public school, they were unable to receive an education. After her son was denied enrollment, Elizabeth used her own home to open a school for minority children in 1854. Initially Elizabeth’s school was only open to African American children, but shortly after it opened she started accepting Asian American and Native American students as well. The Sacramento School Board assumed control over the school in 1855, although they refused to commit public tax revenue to it.

Elizabeth continued to teach and became the first African American public school instructor in California. She retired from teaching after she married Isaac Flood and moved to Oakland. However, seeing the dearth of educational opportunities in Oakland for non-whites, Elizabeth once more opened a school in her home. Meanwhile, she and her husband founded the Shiloh AME Church in the town, Oakland’s first Black church. The church led the way to the purchase of a schoolhouse where she taught until her unexpected death in 1867 at 39. Her successful activism eventually led to school integration in Oakland, and Elizabeth’s daughter, Lydia, was one of the first students at the newly integrated schools.

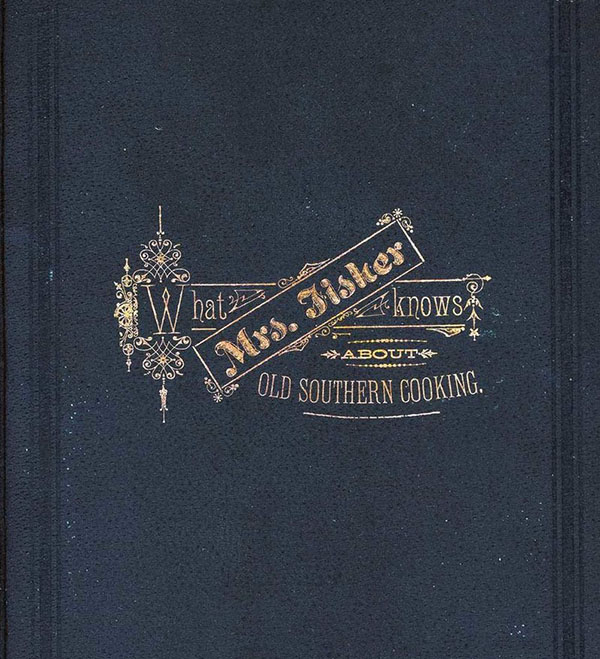

Abby Fisher’s Cookbook Cover

Abby Fisher

Cookbook Author

(1831 – ?)

Born enslaved in South Carolina to an African American mother and a White farmer, Abby grew up and eventually worked as a cook in the kitchen. She married Alexander Fisher around 1859 and together they had eleven children. The family moved to San Francisco, California in 1877 looking for economic opportunity. There, she opened her own immensely successful catering business, called Mrs. Abby Fisher & Co, and won awards for her cooking.

Abby’s Southern cooking was the toast of San Francisco society, and she became only the second African American female cookbook author in America in 1881 when she published What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves. She was illiterate, so she dictated her recipes and anecdotes. Containing 160 recipes, the book is a treasure trove of Southern cooking for historians and was re-printed in 1995. Fisher’s cookbook can still be purchased on Amazon Kindle today.

Mary Ellen Pleasant

Mary Ellen Pleasant

Millionaire and Abolitionist

(1814 – 1904)

Very little is known about Pleasant’s young life and parentage, but she was raised in Nantucket as worked a domestic servant for a White abolitionist family. She was light skinned and, on some occasions, passed herself as White. Through this family, Mary Ellen became involved in the abolitionist movement and worked with the Underground Railroad. She married another abolitionist, James Smith, and gained a substantial inheritance after he died four years later.

In 1849, she remarried and moved to San Francisco. Pleasant started a restaurant that catered to wealthy businessmen in the city, and she would often eavesdrop on these men to pick up investment tips and financial gossip. These bits of information came in handy – Pleasant was able to use them to make a fortune in investments. She used her money and influence to assist African Americans who made it to San Francisco through the Underground Railroad, and later she successfully fought against racial segregation in California through a series of lawsuits. She also gave militant abolitionist John Brown $30,000 to support his raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859.

She eventually began a decades-long business partnership with Thomas Bell and, for unknown reasons, much of her portfolio was in his name. After his death in 1892, Bell’s widow and son sued Pleasant for control of her vast fortune. They successfully painted her as a “scheming mammy” in the press, and she lost her fortune.

In 1901, she dictated her autobiography, The Making of ‘Mammy Pleasant’: A Black Entrepreneur in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco, and she passed away in 1904 as one of San Francisco’s most famous residents.